I've recently been trying to be a responsible adult and be more cognizant of my finances, which means that I've been watching a lot of YouTube videos on the subject.

Back in high school, when I was more optimistic than I am now, I told myself that I would never get into debt. I figured I would always be better off by never owing anyone anything...I would be truly independent. That all changed when I took an AP Economics class my senior year. It was there that I learned about inflation, and how going into debt can potentially be advantageous if you play the game correctly. After that, I still avoided debt, especially credit card debt, but after I graduated college and started working as an engineer I eventually took out loans to buy a car and later a house. My car is now paid off, which is nice, but my house is far from it, which led me into my personal finance knowledge obsession.

If you venture into the online personal finance world, then it doesn't take too long to stumble upon a guy named Dave Ramsey. He has built a veritable empire of personal finance teaching that includes books, seminars, and a call-in radio show. The latter includes a plethora of videos on YouTube, of which I've now probably watched hundreds.

The call-in show is pretty entertaining. It sometimes features people that make you feel a lot better about your current financial situation, as well as some other people who seem to be doing pretty well but Dave nonetheless eviscerates them because they made some decision with which he disagrees...and that usually involves the issue of debt.

Here's an example of a caller who will probably make you feel better about yourself, and who also demonstrates that just because someone has a high salary, they can still be in lots of financial trouble:

What surprised me most about Dave, not knowing anything about him previously, is that he is extremely debt averse. It definitely defied my expectation of a personal finance "expert". He advises against any kind of debt for his listeners with one exception: he allows a mortgage for a home so long as it is a 15 year fixed rate and the monthly payment is no more than 25% of your take-home pay. This is still a pretty conservative amount of debt, especially given that most lenders today are more than happy to offer 30 year mortgage terms with fixed rates. And I don't think he's wrong in making this suggestion, but I don't exactly think he's right either.

Debt Is A Massive Double-Edged Sword

Debt is as American as apple pie and assault weapons, and like both of these things it can be fine if enjoyed responsibly and very bad if enjoyed irresponsibly. According to Nerdwallet, the average American household owes $137,063 in debt, on an average salary of $59,039. That's a lot of debt, but most of it is also mortgage debt, which even Dave Ramsey allows under some conditions. Student loans account for the next biggest chunk of debt, followed by auto loans and finally credit cards.

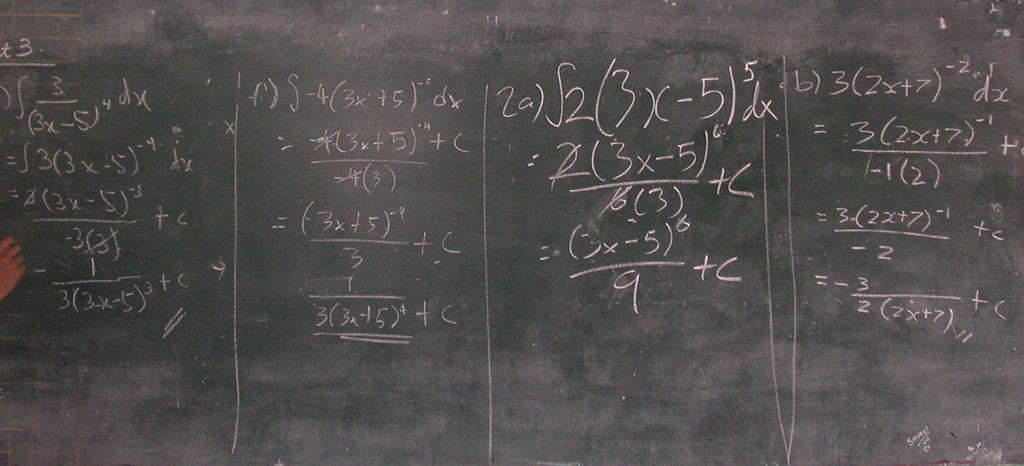

Now, from a mathematical standpoint, the most important question related to debt is "what's the interest rate?" This is a question Dave never asks his callers when they tell him how much they owe, and it's because his philosophy treats all debt as bad. This is especially obvious when you look at his method of paying down debt, which he calls the "snowball" method. Instead of paying off debt in order of highest to lowest interest rate, he suggests paying it off by lowest to highest amount. He admits that this is mathematically wrong, but it has been proven to work because it is psychologically easier for people to stick with.

This really cuts to the core of the entire Dave Ramsey anti-debt philosophy: mathematically sub-optimal, but psychologically tried and true. This makes sense if you've listened to some of Dave's callers, as a decent amount of them are what I call "spending junkies". His advice basically equates to "alcoholics anonymous for people who are terrible with money". AA tells alcoholics to not even look at alcohol...don't be in the same room with it...don't even watch advertisements for it (I'm exaggerating of course...but not by a lot). This is more or less Dave Ramsey's advice with money: only spend it on necessities and don't take out any debt (except for a home) until you've got over $1M in investments and the house is paid off...THEN you can spend a little more freely.

The thing is, not everyone is a raging shopaholic. Much like some people can only drink one beer with dinner and stop there, some people can put all their normal expenses on a credit card and pay it off in full every month. Some people can take out a car loan for a car they could pay for in cash...and invest the rest. Not everyone is a spending junkie, a lot of people are, but some aren't.

In Favor of Mathematical Optimization

I like to think I fall into the latter category. I've never gotten into credit card debt (which is, in most cases, the very worst kind that I think should be avoided at all costs), and I generally live within my means. I'd reckon there are many people like me, and if you are then Dave Ramsey's advice probably falls short.

Now, self awareness is an important skill that needs to be worked on by everyone. If you are the type of person that can't handle debt, if it either makes you unhealthily anxious or causes you to overspend in other areas, then you need to accept that as part of who you are. And if that is who you are, then you should probably keep following Dave's advice (or start following it if you aren't already).

I, however, am an engineer. I'm obsessed with optimization. I like to push the envelope of what's possible while simultaneously acknowledging that the real world is often messy and chaotic, and that "optimal" is seldom realizable. So my goal is to get as close to optimal as possible while leaving enough margin to account for the majority of cases in which things can go wrong. This lead me to embark on a research experiment where I combed data related to home prices, investment yield, and inflation for the past half-century in order to get a feel for what the "right" answer is with regard to home mortgages. Is a 15 year home mortgage really preferable? Is a 30 year mortgage a waste of money on interest? These are the questions I sought to answer. All my data will be given in Part II of this post, but for now let's look at some high-level pros and cons of mortgage terms.

30 Year vs. 15 Year: The Pros and Cons

For starters, let's acknowledge that in most cases a fixed-rate mortgage is preferable, especially if interest rates are decently low like they are now. An adjustable rate gives too much uncertainty. Even if interest rates are high, you can still refinance if rates drop on a fixed-rate.

With that out of the way, the main question in relation to a home mortgage is the length of the term. A 15 year has a few obvious benefits: usually interest rates are a little lower, and because the term is shorter you will pay much less in interest overall compared to a 30 year.

As an example, let's say you have a $200k mortgage. If you financed it for 15 years at 4%, your monthly payment would be $1,479, whereas if you finance for 30 years, the monthly payment is $954. The catch for paying $500 less per month is that you have a mortgage hanging over your head for 30 years, and you end up paying a lot more. For the 15 year term, the total you end up paying at the end is $266k, over $66k in interest. For the 30 year term, you pay over $343k at the end, which is a whopping $143k in interest! And that's for a fairly low interest rate, if interest rates are higher then these numbers get even more ridiculous.

This is where the debt-averse crowd will come in and say "see, the math is all right there, finance for a shorter term so that you pay a lot less in interest!" This is, of course, correct, but it will often be countered with a more nuanced economic argument which brings up my favorite thing to overthink: opportunity cost.

You see, if you finance a house at 4% for 30 years, you will pay several times more mortgage interest than you would on a 15 year mortgage. BUT, your monthly payment is also less, by a fair amount, and you can invest that money in an S&P 500 index fund, which historically returns about 7% per year. Since 7% is greater than 4%, you still in theory come out on top with a 30 year mortgage. In our $200k mortgage example, if you take the extra $500 per month and invest it in the S&P, then you could expect for that to turn into over $600k after 30 years! Exponential growth is fun.

Of course, for a 15 year mortgage you obviously won't have a payment after 15 years, so you can bank your entire monthly payment in investments. If you do this, then you'll end up with $446k in investments at the 30 year mark. Subtracting out the amount you paid in interest for the 30 year investments gives you $450k, while subtracting out the interest from the 15 year investments gives $380k. While both numbers are relatively close, you can clearly see that investing for 30 years with a 30 year mortgage will allow you to end up with more money than investing for 15 years with a 15 year mortgage, even though you pay much more interest with the 30 year mortgage.

This is where the more mathematically savvy folks puff up their chests and say "ha! A 30 year mortgage IS better if you can get a decent interest rate!" If it's on an internet forum, then they'd likely include more expletives insulting the intelligence of Dave Ramsey die-hards.

But the Dave Ramsey crowd usually has one more trick up their sleeve...an ace in the hole that they will pull out when the mathematical purists are doing their smug, awkward happy dance. "Yes...but you aren't accounting for risk."

And they are right. The S&P 500 averages about a 7% return per year, but that doesn't mean that every year your stocks will be up 7%. Some years it's up a lot, some years it's down a lot. There are no guarantees. If you have a paid off house, then your financial worries diminish quite a bit. Aside from maintenance, basic living expenses, and property taxes, you don't really have anything else on which to spend money. As long as you have a mortgage, it's a noose around your neck. If you fail to pay then your house can be taken away from you.

And that's usually where the conversation ends, with no one's mind changed. The debt averse Dave Ramsey crowd will continue to pay off their mortgages as fast as they can in order to achieve debt-free nirvana, and the mathematical purists will continue to live dangerously for the sake of supposed financial optimization.

I, however, wasn't satisfied with this non-conclusion. I know that there are risks to debt, and I also know that there are risks to investing. But if I pooled some data from the past, could I understand the risks...could I quantify the risks?

I, however, wasn't satisfied with this non-conclusion. I know that there are risks to debt, and I also know that there are risks to investing. But if I pooled some data from the past, could I understand the risks...could I quantify the risks?

That is what I set out to do, and in Part II of this post I will reveal what I found. Stay tuned.